Most students approach past papers like a video game: collect points, move to the next level, rinse and repeat. They complete a paper, check answers against the mark scheme, and move on. This wasted opportunity leaves grades stagnant.

Top students treat past papers differently. They analyze them. They reverse-engineer mark schemes. They extract patterns examiners use year after year. Students who apply strategic past paper methodology show grade improvements of 1.5 to 2 full levels compared to those who simply practice completing papers.edugravity

This article reveals the exact framework high-performing A Level students use to turn past papers into a precise, data-backed revision tool.

Need expert learning support? Check out our online tutoring

What Students Are Asking About Past Papers

The confusion around past paper practice shows up in forums across Reddit and student communities every exam season.

Students ask whether to complete papers with notes available or under timed conditions first, and how many times they should repeat the same paper. Many waste papers by attempting them without proper preparation, then feel defeated when scores are low.

Others make the opposite mistake. They read through papers without actually attempting them, convincing themselves they “could” answer questions if they tried. This false confidence crumbles in the actual exam.

Education experts consistently point out that mark schemes reveal keywords and phrases that secure marks, yet most students ignore this goldmine of information.

The real question isn’t “should I do past papers?” It’s “how do I use them to actually improve my grade?”

Why Past Papers Are Intelligence Tools, Not Just Practice Tests

Past papers contain embedded intelligence. Every question reveals something about exam structure, examiner preferences, and assessment criteria. Topic weightings follow patterns. Question formats repeat. Mark schemes reward specific answer structures.

Most students see past papers as a checkbox: “Did past papers? Yes.” Top students see them as a diagnostic system that reveals exactly where to invest study time for maximum grade impact.

Here’s the difference: Surface-level approach (most students) wastes time on papers without extracting the intelligence. Strategic approach (top students) uses papers to identify patterns, build exam technique, and target weaknesses with surgical precision.

Most students treat past papers as simple practice, but top performers treat them as data sources. The comparison below highlights the critical difference in mindset.

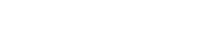

Stop passively reading and start actively solving—this comparison shows why active recall is the superior study method.

Shifting from the ‘Surface’ approach to the ‘Strategic’ approach transforms a past paper from a simple test into a powerful diagnostic tool.

The Three-Phase Strategy: When and How to Use Past Papers

Top students don’t jump straight to full past papers. They follow a proven sequence that builds competence gradually.

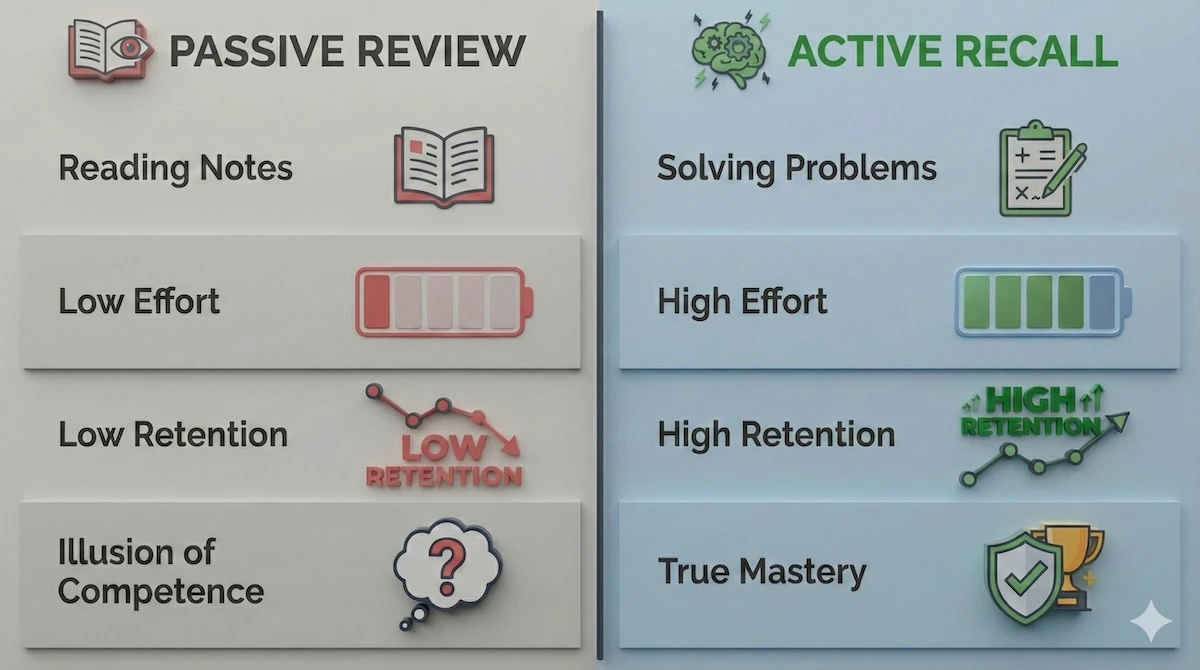

To help you visualize the roadmap from novice to expert, we have broken down the strategy into three distinct phases. The following flowchart illustrates how you should progress from open-book mastery to strict exam conditions.

Follow this 3-stage progression to transform past papers from simple practice into a powerful diagnostic tool.

Notice how the focus shifts from accuracy in Stage 1 to speed in Stage 2, and finally to detailed diagnostics in Stage 3.

Phase 1: Topical Questions (First 6-8 Weeks of Revision)

Start with topic-specific past paper questions, not full papers. This phase builds foundational understanding before the pressure of timed, full-paper conditions. You strengthen individual topics while maintaining focus and avoiding overwhelm.reddit+1

Arrange topical questions by concept, not by year. Complete all questions on one topic before moving to the next. When you’ve mastered a topic through topical questions, you understand the content at depth. This prevents you from wasting time re-learning concepts during full paper attempts.

How long: 4-6 weeks into revision (approximately 3 months before exams).

Phase 2: Diagnostic Full Papers (Weeks 7-10 of Revision)

Once topical knowledge is solid, complete 1-2 full papers under timed, exam-style conditions. Don’t analyze these papers immediately. Instead, use them diagnostically to identify which topics cause problems when combined with time pressure and mixed question formats.reddit

This reveals your actual exam weaknesses, not just theoretical gaps. A student might master Thermodynamics in isolation but freeze during a mixed-topic paper when questions appear in different orders than they studied them.

Mark these papers without despair. The goal is identifying patterns: Which question types trip you up? Where do you lose time? Which topics cause calculation errors under pressure?

Phase 3: Strategic Practice and Refinement (Final 4-6 Weeks)

Now you know your weaknesses. Return to topical questions specifically targeting these areas. Practice the same question type repeatedly across different years to build pattern recognition and speed.edugravity

Only after this targeted improvement should you attempt more full papers. This time, these papers serve as progress checks, not discovery tools. Track improvement over time rather than chasing numerical scores.

Read more to get instant, accurate homework help

The Secret Weapon: Topic Frequency Mapping

This is what separates A students from A* students.

Create a spreadsheet analyzing the past 5-7 years of papers. For each topic, record:

- How many times it appeared

- How many marks were allocated

- Whether it appeared in certain papers more than others

- Question format (short answer, calculation, essay)

Example: In A Level Chemistry, if “Le Chatelier’s Principle” appears in 6 of the last 8 papers, accounting for 12-15 marks each time, this topic deserves significantly more revision time than a topic appearing once.

High-frequency topics receive priority study time. Low-frequency topics get foundational understanding but less intensive practice. This allocation matches exam reality rather than textbook chapter ordering.edugravity

Students who skip this step treat all topics as equally important. This wastes revision time on low-impact content. Students who complete frequency mapping spend revision hours exactly where the marks are.

Instead of guessing which topics are important, create a data-driven map. Here is an example of how to structure your Topic Frequency Spreadsheet to reveal where the marks really are.

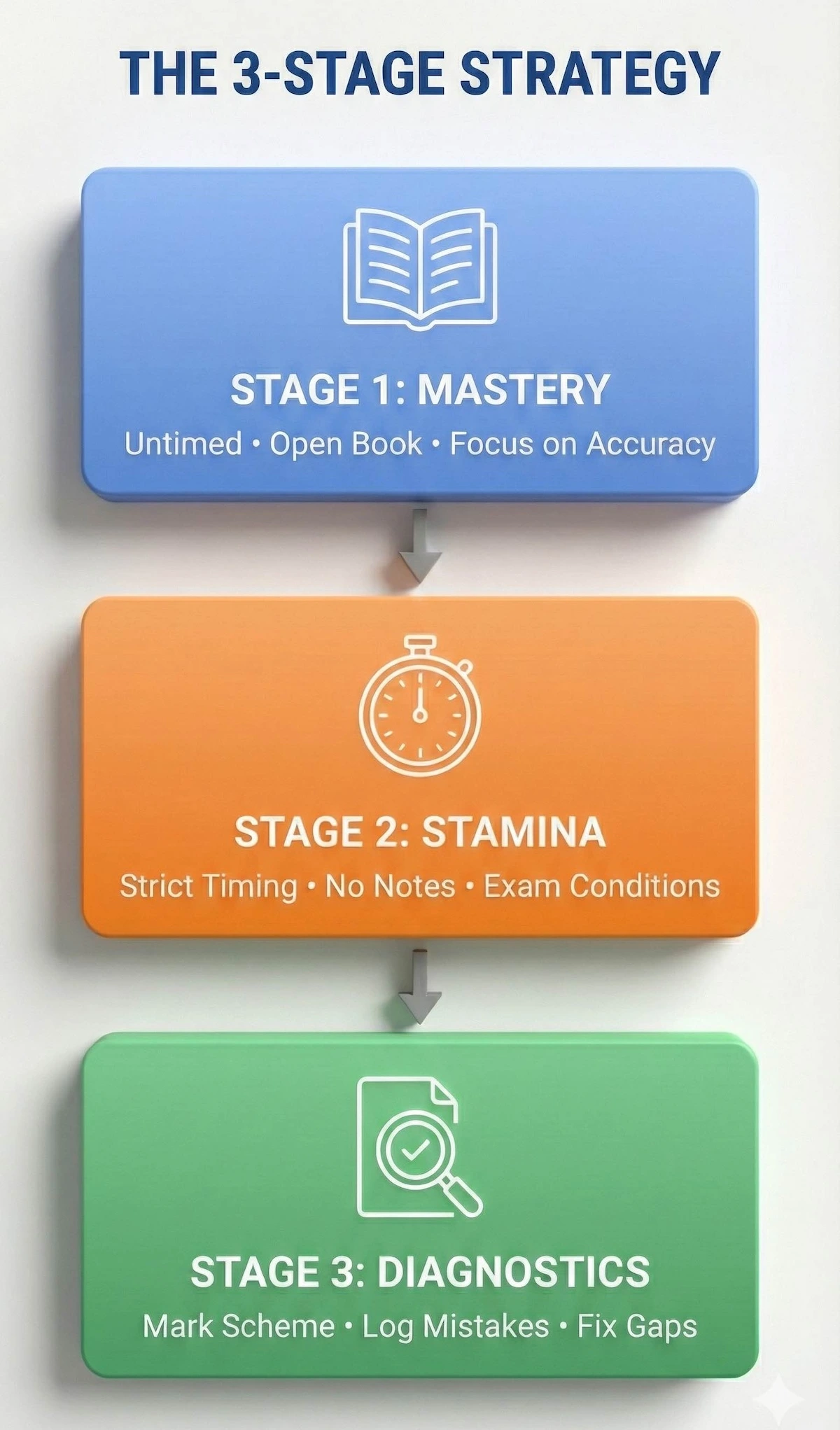

Don’t just count your marks—categorize your errors using this Mistake Log structure to identify exactly what to fix.

By visualizing the data this way, you can see exactly which topics—like ‘Le Chatelier’s Principle’ in our example—deserve 80% of your revision time.

Reverse-Engineer the Mark Scheme

Examiners don’t award marks randomly. They follow patterns. Top students study these patterns.

Rather than only checking if answers are right or wrong, work backwards from the mark scheme. For each question:

- Read the mark scheme first

- Identify the exact phrases, concepts, and structure examiners reward

- Compare top-scoring sample answers to identify successful response patterns

- Notice what low-scoring answers omitted

This reveals the “hidden curriculum” of what examiners actually want. A physics question might ask “Explain how velocity changes,” but the mark scheme only awards full marks if you mention “direction and magnitude” specifically. Without reading the mark scheme first, you miss this language requirement.

Students who do this build accurate mental models of examiner expectations. They stop guessing and start writing answers designed for maximum marks from day one.edugravity

The Marks-Per-Minute Framework

Time pressure separates high performers from middle-tier students. Top students manage time strategically using data.

After completing a few papers, analyze your performance by marks-per-minute. Some question types might offer 4 marks in 3 minutes. Others might require 5 minutes per mark. Questions with high marks-per-minute ratios deserve less time investment (do them quickly). Questions with low ratios deserve more focused effort.

Track your personal completion time for each question type across multiple papers. Where do you consistently spend too much time relative to marks available? Where do you rush and lose marks? Adjust your strategy accordingly.edugravity

For example: If you spend 8 minutes on a 3-mark question but 2 minutes on a 5-mark question, you’ve inverted the optimal strategy. Identify this pattern and practice increasing speed on high-value questions while accepting slightly lower accuracy on lower-value questions if necessary.

This isn’t guessing. It’s time optimization backed by your own performance data.

Mistake Analysis: The System That Works

Most students review past papers once, note mistakes, and forget them. Top students create systematic mistake-tracking systems that prevent repeated errors.

Categorize your mistakes:

- Conceptual gaps (don’t understand the principle)

- Calculation errors (understand concept, made arithmetic mistakes)

- Time management (ran out of time, didn’t attempt)

- Misreading questions (misunderstood what was asked)

- Incomplete answers (understood concept but didn’t include all required elements per mark scheme)

Categorizing your errors is the only way to stop repeating them. Use the following classification system to tag every mistake you make in your log.

Combat the forgetting curve by scheduling reviews at these specific intervals after completing a past paper.

If you notice your log filling up with ‘Calculation Errors’ rather than ‘Conceptual Gaps,’ you know you need to focus on accuracy drills rather than re-reading textbooks.

Track these categories across multiple papers. A student making 5 conceptual errors, 8 calculation errors, 2 time management errors, and 3 misreading errors should focus revision heavily on conceptual gaps and calculation practice, not on speeding up.

Use digital tools: Google Sheets, Notion, or Anki for systematic tracking. Screenshot challenging questions, store them with mark scheme solutions, and review them during spaced repetition sessions. This creates a personalized question bank of your recurring weak points.

Use Examiner Reports: The Free Intelligence Resource

Every exam board publishes examiner reports alongside past papers. These documents detail what candidates did well and what caused widespread problems. This is free insight into examiner expectations and common student mistakes.

Read the examiner report after completing a paper, not before. Look for patterns in what the report describes as “common errors” and “areas needing improvement.” If the report notes that 80% of candidates lost marks by not showing working for calculations, this becomes a priority for your answer technique.

Examiner reports also reveal which topics seemed harder for cohorts nationally. If the Physics report indicates weak performance on thermal energy transfer, this signals the topic deserves extra attention.

Spaced Repetition: When to Return to Difficult Questions

Don’t attempt the same paper twice in the same week. Your brain needs time for forgetting to occur, then recovering that information requires stronger memory encoding.

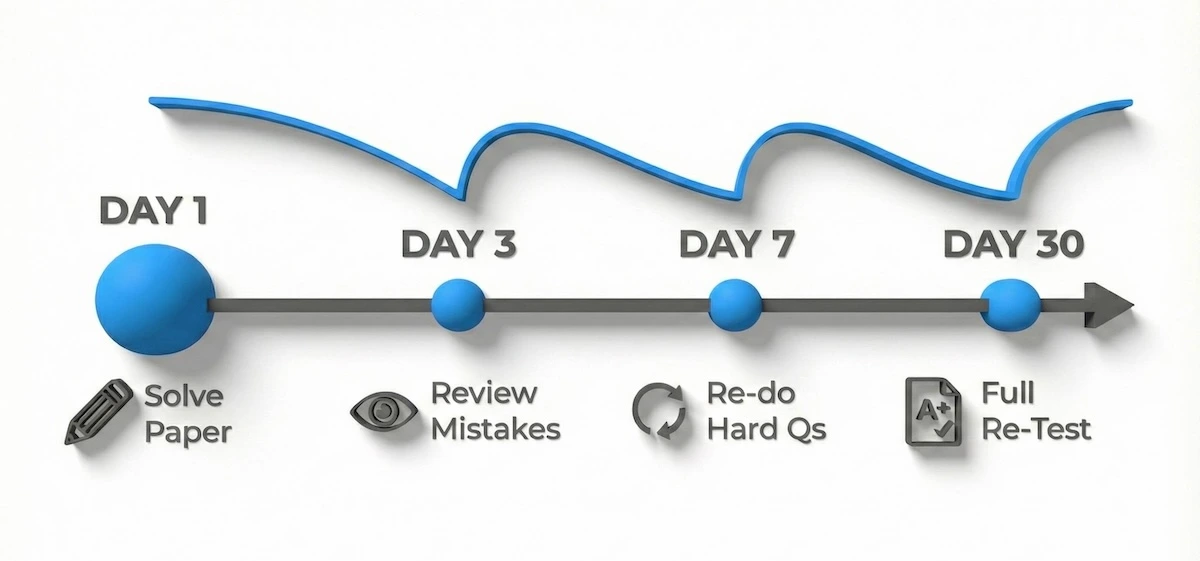

Use the 2-3-5-7 method: Review difficult questions after 2 days, then 3 days later, then 5 days later, then 7 days later. This spacing leverages the Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve, which shows how memory fades over time. Reviewing just before you forget maximizes retention.

The ‘2-3-5-7 Method’ is designed to combat the forgetting curve. The timeline below shows exactly when to schedule your reviews for maximum long-term retention.

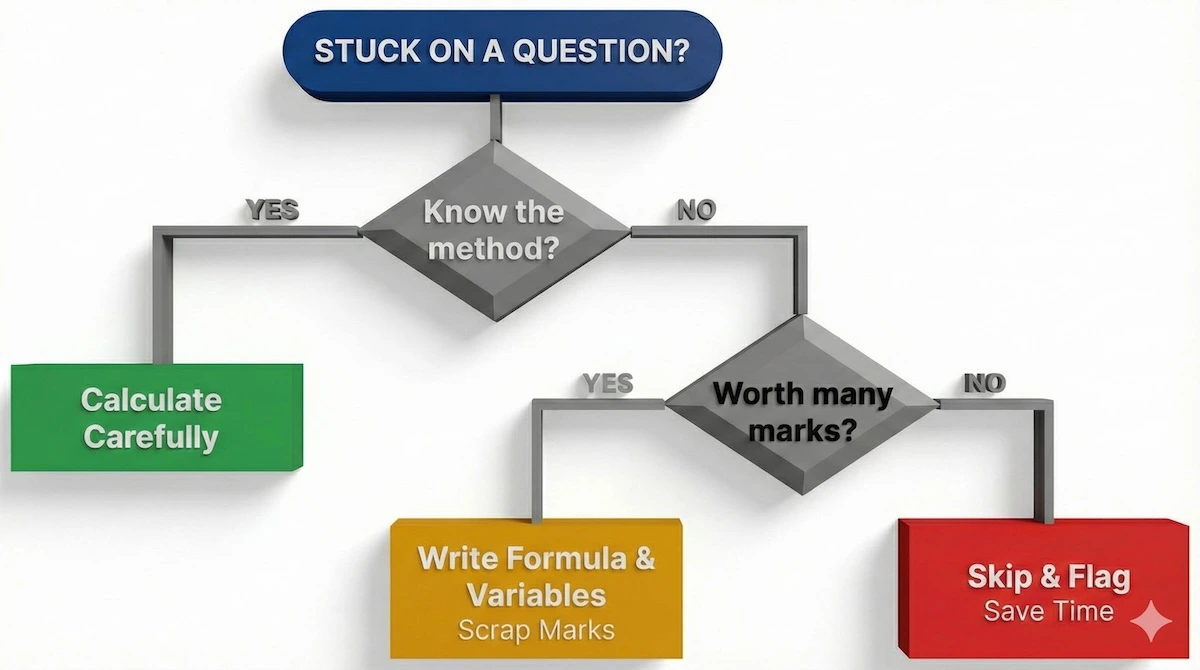

Memorize this decision tree to prevent panic and maximize marks when you encounter a difficult question in the exam.

Sticking to these specific intervals—especially the Day 3 and Day 7 reviews—ensures that difficult concepts move from your short-term working memory into long-term storage.

This isn’t passive review. Use active recall: attempt the question again without looking at your previous answer. Only then check if you’ve improved.

The Timeline: When to Start Past Papers

Academic research and student consensus agree: Start serious revision 3-4 months before your first exam.

Within this timeline:

Months 3-2 before exams: Topical past paper questions while completing content. Don’t wait until you’ve finished all topics. As soon as you finish a topic, practice topical questions on it.

Month 2-1 before exams: Increase past paper practice. Complete diagnostic full papers. Identify weak areas. Return to targeted topical practice.

Final 4 weeks: Intensive full paper practice under timed conditions. One paper every 2-3 days. Space out difficult papers using the 2-3-5-7 method. Practice exam technique refinement rather than new learning.

This timeline prevents cramming while building progressively harder skills.

How Many Past Papers Is Enough?

The consensus from Reddit and academic sources: 5-6 quality past papers per module, analyzed thoroughly, is more effective than 15 papers completed superficially.

Don’t aim for a magic number. Aim for depth. One paper analyzed for 4 hours (topic frequency mapping, mark scheme reverse-engineering, mistake categorization, examiner report review) provides more value than three papers completed in 3 hours total.

If you’re taking three A Levels with multiple papers each, completing 15-20 full papers total throughout the revision period is realistic and sufficient when combined with topical practice.

Quality over quantity consistently produces higher grades than quantity alone.

Common Mistakes Students Make With Past Papers

Mistake 1: Ignoring time gaps. Completing three past papers in one week provides limited benefit. Space them across weeks to allow improvement implementation between attempts. Cramming papers intensively doesn’t replicate distributed practice benefits.

Mistake 2: Quantity without analysis. Completing 20 papers without strategic review wastes time. Five papers with deep analysis outperform 20 papers with surface-level checking.

Mistake 3: Starting full papers too early. Beginning with full papers before mastering topics individually creates frustration and false performance indicators. Topical work first builds confidence and prevents false conclusions about your ability.

Mistake 4: Avoiding difficult questions. Students tend to skip challenging questions and focus on easier ones. This inverts the learning benefit. Difficult questions teach the most. Embrace them as learning opportunities.

Mistake 5: Ignoring the mark scheme. Checking only if answers match the mark scheme misses the deeper intelligence about examiner expectations. Read mark schemes actively, noting exact language and structure examiners reward.

Mistake 6: Not tracking progress. Without systematic records, you can’t identify improvement or adjust strategies. Track scores, accuracy by topic, time management, and mistake categories across papers to see genuine progress.

Check out smart test prep solutions to score higher

Subject-Specific Past Paper Tactics

Different A Level subjects need different approaches to past paper practice.

Mathematics and Sciences: Focus on showing all working. Even when you know the answer, write out every step. Mark schemes award method marks even when final answers are wrong. Practice identifying which formula or principle each question tests. Create a formula sheet while doing papers, noting which equations appear most frequently.

Essay Subjects: Time yourself writing full essay responses, not just planning them. Your writing speed matters. Read examiner reports to understand what separates a grade B essay from a grade A essay. It’s usually specificity of evidence and depth of analysis, not length. Practice integrating quotes or data smoothly rather than dropping them in randomly.

Mixed-Format Papers: Break these into sections during practice. Do all the short-answer questions from multiple papers to build pattern recognition. Then practice extended writing separately. This focused practice is more efficient than always doing full papers.

Beyond Just Practicing: The Review Mindset

Here’s what separates students who improve dramatically from those who plateau despite doing many papers.

Top students treat review as equally important as practice. After marking a paper, they don’t just note their score. They ask better questions: Why did I lose marks on this question? Was it timing? Was it not understanding what the question asked? Was it a content gap? Was it poor exam technique?

Different problems need different solutions. Content gaps need targeted revision. Technique problems need more practice with similar question types. Time management issues need stricter timing practice.

They also look for their “silly mistake” patterns. If you consistently lose marks for forgetting units in calculations, that’s not random. It’s a systematic error. Fix it by creating a personal checklist you run through for every calculation question.

Reading examiners’ reports for past exams provides amazing insight into what examiners wanted to see from students and where students went wrong. These reports highlight recurring mistakes across thousands of students. Learning from others’ errors saves you from making them.

Making Past Papers Work for Your Schedule

You don’t need six hours a day for effective past paper practice. Strategic practice beats marathon sessions.

Break papers into chunks if time is limited. Do one section per day rather than waiting for a free three-hour block that never comes. Just ensure you eventually practice full papers under timed conditions before exams.

Use papers diagnostically. If you’re short on time, do all question 1s from multiple papers (the “easy” questions). This builds confidence. Or do all the highest-mark questions to practice the challenging content. Then fill in gaps as time allows.

Study with others strategically. Complete papers individually, then meet to discuss difficult questions. Teaching a concept to someone else or hearing their explanation often clarifies understanding faster than solo review.

Key Points to Remember

Past papers are intelligence tools, not just practice tests. Analyze them strategically for 1.5-2 grade level improvements. Start with topical questions, then move to full papers once foundational understanding is solid. Reverse-engineer mark schemes to understand examiner expectations. Use topic frequency mapping to prioritize revision time toward high-impact content. Track mistakes systematically by category rather than just noting right or wrong. Read examiner reports to learn from widespread student errors. Spread past paper work across weeks to leverage spaced repetition benefits. Quality analysis of 5-6 papers beats superficial completion of 20 papers. Focus revision time on your recurring weak areas using targeted topical practice between full paper attempts.

The A Level students who outperform their peers don’t work harder. They work smarter. They extract intelligence from past papers rather than simply completing them. This framework turns a standard revision tool into a precision weapon for exam success.

******************************

This article provides general educational guidance only. It is NOT official exam policy, professional academic advice, or guaranteed results. Always verify information with your school, official exam boards (College Board, Cambridge, IB), or qualified professionals before making decisions. Read Full Policies & Disclaimer , Contact Us To Report An Error