What is kinematics

Before we study kinematics equations, it is a good idea to understand what Kinematics is.

When we observe nature, we see many objects in motion. From experience, we recognize that motion represents the continuous change in the position of an object with time. We study dynamics in two parts kinematics & kinetics. In kinematics, we study motion in terms of space and time without knowing the cause of motion (the forces that caused the motion). In kinetics, we are also concerned about the cause of motion (forces).

(If you want private 1:1 online tutoring or homework help from an experienced physics tutor at an affordable rate, feel free to WhatsApp us. We will get you started right away).

Kinematic equations list

…(1)

…(2)

…(3)

…(4)

Equations (1), (2) & (3) (and sometimes (4)) are the equations of motion with constant acceleration. These are also known as equations of kinematics or kinematic equations.

velocity of particle along x-axis of time t

velocity of particle along x-axis at t = 0

constant acceleration of particle along x-axis

x: position of the particle at time t on the x-axis

position of particle at time t = 0 on the x-axis

t: it represents general time.

How to use kinematic equations

The kinematic equation for time, the kinematic equation for velocity

we have first equation of kinematics

This expression enables us to determine the velocity at any time t if the initial velocity, the acceleration, and the elapsed time are given.

We have second equation of kinematics .

This expression enables us to determine the distance traveled during any time t if the initial velocity, acceleration, and time elapsed are known.

We have a third equation that lets us determine the final velocity if the initial velocity, acceleration, and displacement are known.

Solved problems on each kinematic equation

Example 1

An athlete takes 20 sec to reach his maximum speed of 18.0 km/h. What is the magnitude of average acceleration?

Ans. Her athlete is running along the x-axis with constant acceleration; we can use

Therefore, the magnitude of the average acceleration is 2.5 m/s2.

Example 2

An object having a velocity of 4.0 m/s is accelerated at the rate of 1.2 m/s2 for 5.0 sec. Find the distance traveled during the period of acceleration.

Ans. Suppose the object is moving along the +ve x-axis.

Assuming that the initial location of the particle is at the origin.

Here,

,

,

.

Using kinematics equation,

Example 3

A person traveling at 43.2 km/h applies the brake giving a deceleration of 6.0 m/s2 to his scooter. How far will it travel before stopping?

Ans. Suppose the person is traveling along the positive x-axis and initially that person was at the origin (x = 0).

He is moving along a straight line with constant negative acceleration.

Using kinematics equation,

Here,

[because

]

So, the person will travel a distance of 12 m before stopping.

The kinematic equations for projectile motion

The projectile’s motion can be discussed separately for the horizontal and vertical parts. We take origin at the point of projection. The instant when the particle was projected is taken as t = 0. The plane of motion is taken as the x-y plane, the horizontal line OX as the x-axis and the vertical line OY as the y-axis. Vertically upward direction is taken as the positive direction of the y-axis.

We have,

Horizontal motion

, we have

Again, [Here,

]

Vertical Motion

The acceleration of the particle is g in the downward direction.

Thus [Here,

]

We can write,

and

Again,

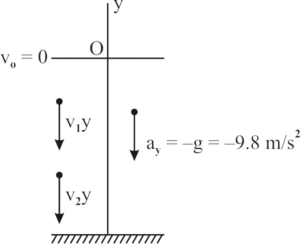

Kinematic equations for free-fall

A typical example of motion in a straight line with constant acceleration is the free fall of a body near the earth’s surface.

Here, we have taken the origin O at the starting point and the upward direction as positive. Assuming the initial portion co-ordinate and initial velocity is

.

The y-acceleration is downward (i.e., along the –ve y-direction) therefore, .

After time t, its position co-ordinate can be written as

Here in this case,

After time t, its velocity co-ordinate

Here

We can also write,

Here,

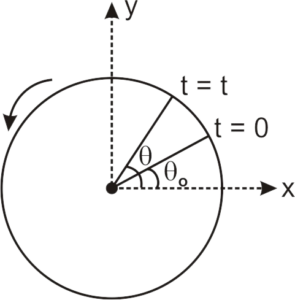

Kinematic equations for rotation

When a body revolves about a stationary axis (usually z-axis), the position of the body is described by an angular position coordinate . If the angular acceleration is constant, then

,

and

are related by simple kinematic equations.

Kinematic equations in the case of rotation are as follows:

Here, Angular position of the body at time t = 0

Angular position of the body at time t = t

Constant angular acceleration of the body

Angular velocity of the body at time t = 0

Angular velocity of the body at time t = t

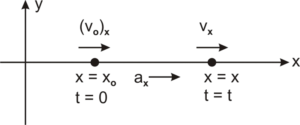

Kinematic equation derivation using calculus

Let a particle is moving along x-axis. Initially assuming particle was at and particle has initial velocity

.

The particle has a constant acceleration along the x-axis. from the definition of acceleration.

Integrating both sides with proper limits

Again from the definition of velocity

Now, integrating both sides with proper limits

Again starting from,

Now, integrating both sides,

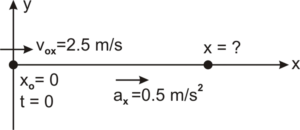

Example

A particle starts with an initial velocity of 2.5 m/s along the positive x-direction and accelerates uniformly at the rate of 0.5 m/s2. Find the distance traveled by it in the first two seconds.

Ans. Let particle stats its motion from the origin with an initial velocity of

Using,

Now, integrating both sides,

Again using

Now, integrating both sides,

Since the particle does not turn back, the distance traveled equals 6 m.

Kinematics equation for nonuniform acceleration

If the acceleration of a particle during its motion does not remain constant, then both motion and acceleration are nonuniform.

As by definition,

If x is a function of time, the second derivative of displacement with respect to time represents acceleration.

If velocity is a function of position, then by chain rule of differentiation.

Example

The acceleration of a particle moving in a straight line varies with its displacement

. The velocity of the particle is zero at zero displacements. Find the corresponding velocity displacement equation.

Ans. We have,

Now, integrating both sides with proper limits

.

Resources

Kinematics equations Calculator

While there are many online calculators on kinematics equations, we suggest you use Physics Catalyst’s calculator on the same.

Online tutoring and homework help services in Kinematics equations and related topics in Physics

My Engineering Buddy provides excellent online physics tutoring services that cover topics like kinematics equations and much more.

Author

-

20 years of experience teaching high school and college physics to students across the globe.

When not teaching or mentoring, I write informative articles in physics and related subjects. So far, I have written more than 200 articles on different topics in physics. Apart from physics, I am proficient in engineering statics, dynamics, and calculus. I love spending time with my kids and listening to old Hindi songs.